News of Tiant’s death at age 83 on Tuesday sparked vivid memories not only for those who witnessed his performances at Fenway Park but also for generations who never did. To see the right-hander’s highlights is to recognize the magic that set Tiant apart from his contemporaries and rendered his style and actions on the mound almost incomprehensible now.

Tiant often described promotion as an act of will – an interpretation of “The Old Man and the Sea” that unfolds every four days. He had a strong drive to win, but he felt an unrelenting purpose not only in the result but in the competition itself.

“When I throw the ball, that’s my game. I didn’t want to get out of there,” Tiant once recalled. “My dad used to tell me when I started pitching, when I was growing up, he said, ‘You don’t start something you can’t finish.’” When you go there, you better stay there and you better finish the game. “

Get the starting point

A guide to the most important morning stories presented Monday, Wednesday and Friday.

The result was an astonishing 187 complete games, a number Tiant recalled accurately and proudly in his conversations. For context: In the past five years combined, there have been 178 complete games in the major leagues. In 2024, the pitchers combined to throw 28 complete games, just three more than Tiant threw in 1974 alone.

His complete games were not only a product of strength — especially after a shoulder injury in the early 1970s, which not only led to a shuffle between organizations, eventually landing Tiant in Boston, but also impaired his fastball ability — but also of creativity.

Like all pitchers throughout baseball history, Tiant suffered a strikeout “a few times through the order” in games. Hitters improved with each successive look at the right-hander.

But in Tiant’s case, the punishment was gradual. As a starter, he held hitters to a .624 OPS the first time he faced them, a .671 mark his second look, a .698 mark the third time, and a .724 OPS the fourth time or later. He was more vulnerable but never helpless as the game progressed, largely because he had a great sense of how to keep batters guessing even when they saw him multiple times.

“If you hit me, you’ll never see this pitch again. No way, Jose.” “When the hitter sees you three or four times, it’s not easy to fool you anymore. … You have to do what you can — change your pitching mechanics for the hitters you have to face, change your pitches.

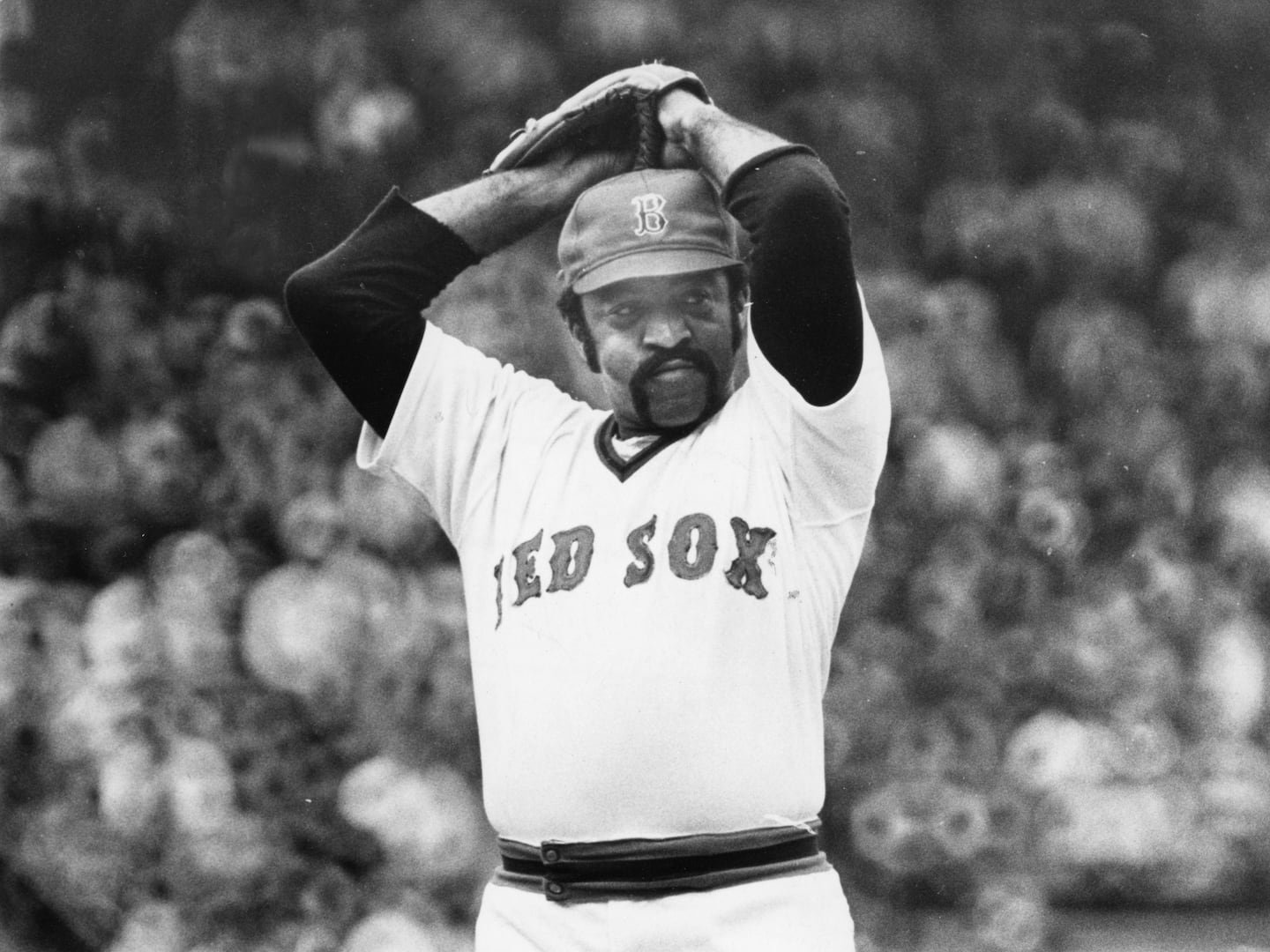

Tiant manipulated time and space with his delivery, rotating with his back to the hitter, then varying the rhythm with which he unraveled, sometimes hesitant, sometimes accelerating. When he released the ball, he did so from a variety of arm angles — over the top, three-quarters, off the sidearm — making hitters wonder if they were seeing a double.

His array of throws — fastballs, slow-moving Bugs Bunny curveballs, more obvious hooks, sliders, palm balls, and sometimes even knuckleballs — came with tremendous control and varying speeds. Hitters could only guess the shape, location and speed of what they were facing.

Pitching now revolves around “tunneling” – creating deception by throwing multiple pitches from the same release point. There is a cruel sorcery in the pairing of sinker and slider that starts out on the same flight only to have the hairpin turn in opposite directions.

But Tiant presented something more complex, confronting fighters not with narrow tunnels but with mazes they rarely had time to solve. Hitters had to look for not one but several tunnels, which often led to confusion.

“It’s a mathematical algorithm that he had more dramatically than any other player,” Lee said of his former teammate’s ability to disrupt opponents’ timing. “He’s got pinpoint control, he can spin, he can get open quickly and make a changeup, he can get open slowly, get a little low, throw a four-seamer up and inside, and he can get over the top with an overhead kick. Demon.”

Tiant’s brilliance in the 1975 World Series was front-page news in the Boston Globe

The result was astonishing – a form of wire-to-wire showmanship for a juggler who always seemed to have a new trick at his disposal, fueled by the endurance he acquired through his daily running up and down the outfield stairs from left field to infield. The correct field.

“There was no one at the club, nor any other player, who worked harder than me,” Tiant said.

It was all part of the performer’s willingness to give his all while on stage – a commitment that was felt by the spectators and thus sparked an emotional investment like few others.

Tiant wowed audiences in a way that can still be felt more than 40 years after his last big-league performance, helping to explain his enduring fame and the sense of loss at Picasso’s death.

Alex Speier can be reached at alex.speier@globe.com. Follow him @AlexSpear.