Dragon Age: The Veilguard has plenty of rewards for Dragon Age: Inquisition fans who have endured the decade-long wait between the two games. The first to appear will be the opportunity to recreate your version of the Inquisition player character for its appearance in Veilguard.

As one of those patient fans, I’ve spent 10 years reminiscing about my adventures in Dragon Age: Inquisition. It’s no surprise that sitting down to build my own Inquisitor generates a wave of feelings for this character and the story I crafted for them a decade ago – that is, after all, the traditional emotional hook at which BioWare’s best games excel.

But it wasn’t just nostalgia that made me feel emotional as I modified the detective’s hair, face, and details of her background: the idea was that even though she might not be a main character anymore, her story still continued. I was almost 30 when I played Inquisition, and now I’m almost 40. But my Inquisitor is also 10 years older, judging by the time the Veilguard was appointed – and damn, Inquisitor Haleth Lavellan, Herald of Andraste and Comtesse of Kirkwall. Still in the game. Literally, yes, but more importantly, figuratively.

The classic hero story is the province of young and inexperienced adventurers, especially in the RPG style of high fantasy threads that occupy so many games. The epic hero’s story attempts to end happily ever after, usually at the moment when the quest goal is reached, because that is where all the narrative tension and catharsis is found. It makes sense! (There are lots of exceptions to this, but they are just that: exceptions.)

But role-playing games can also be a great place to explore an adventurous life, and not just that weird summer I had a tadpole in my head. And in some ways, I set myself up to have a lot of feelings about older heroes and legacies when I turned on Veilguard by playing a game that had clearly talked about that before. I bridged the gap between replaying Inquisition before Veilguard and actually playing Veilguard (thanks to early code from BioWare) by immersing myself in Worldwalker Games’ Wildermyth.

One of Wildermyth’s many procedurally generated stories excels at Image: Worldwalker Games

Wildermyth is a tactical RPG in which you play a series of procedurally generated adventures with teams of procedurally generated (and highly customizable) heroes. You follow each hero from a brave and inexperienced adventurer through the ups and downs of a unique story designed to have the atmosphere of a long-running fantasy campaign. You watch your characters experience victory, loss, transformation, and for some, even love, children, and old-age retirement. Then, when their story ends, you can start a new arc, with a new threat, and build a party that is a mix of new adventurers, veteran characters from your last game, and even children of your old party.

I was still thinking about how powerful these ancient mechanics had endeared me to the relatively bland Wildermyth characters when I booted up Dragon Age: The Veilguard and started making my own Inquisitor game. This isn’t the first time Dragon Age has let you build up your old PC so you can appear in a new game – Inquisition surprises you with a mid-game trip to the character creator to make your own Hawke, the player character in Dragon Age 2. But with Hawke, you You come into contact with them only a year or so after the uncertain end of their game. There’s no gap there, no call to ponder how 10 years have passed since the Inquisitor emerged from the Breach and brought the fractured nations of Southern Thedas back together… And yet, their story is far from over.

When I and other players in my decade-long tabletop campaign put our heads together about our characters, a recurring theme of our daydreams was imagining the lives they would live after we closed the campaign book (note, don’t tell us Jimin, the story isn’t over yet). Now, part of this is that we’re completely showing our ages: we all cluster around 40, and we’ve been playing characters in that classic fantasy hero age range of about 20 to about 30 this whole time. We know there’s a lot of life on the other side of this divide, and we want it for them, too.

But while I respect and support my friends who are determined to settle down and return home, I long for something different. I want to know that there are more adventures in her future. With Inquisitor, Dragon Age: The Veilguard gives me that. There has been an end to the Inquisition story, but the Inquisitor is still here, making moves. (What kind of moves? I had to play the game to find out.)

Pictured from left to right: Child, legend. Image: BioWare/Electronic Arts Image: BioWare/Electronic Arts

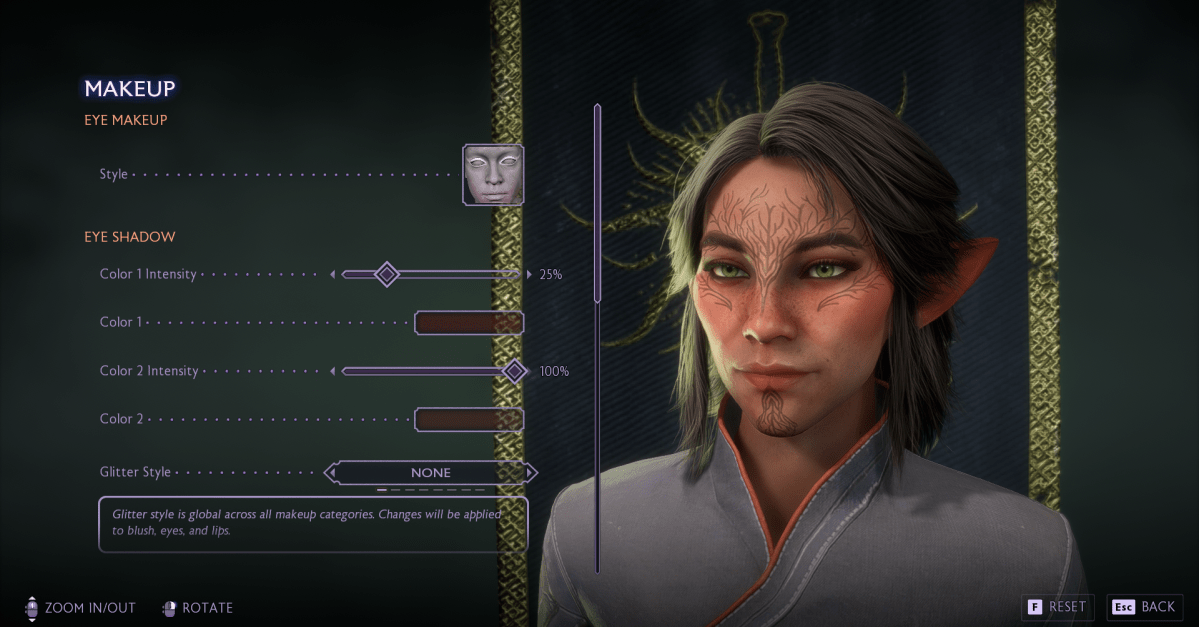

In the character creator, I did my best to mimic the Inquisitor’s face (or at least how she was designed in Veilguard’s smoother art style), but I also made a bunch of thoughtful changes. Drier skin, gray hair, different cut – no more braids, she now works with a prosthetic hand, and while she could get someone to do it for her, I see her wanting more independence. She locked in her pivotal decisions about the Inquisition, her romantic partner (the man every smug nobleman in the smug ball of humanity wanted to hit), and she captured her voice, the low British tones of actor Alex Wilton Regan.

I’m quite familiar with Regan’s voice, after all the hours I’ve spent on Inquisition, but I pressed the audio test button anyway, for kicks. “It’s good to see you again,” my detective said.

That was a cheap shot, BioWare, but it hit the mark. It’s good to see my Inquisitor again, and it’s good news for all those on the other side of the Untested Fantasy Hero era to see that she still has a hand (no pun intended) in Thedas’ case.