Earlier this month, former President Trump was asked a revealing question at the Economic Club of New York: What would he do about child care?

Trump’s bumbling response — when he said “child care is child care” and then talked about definitions — reflects how rarely men in the halls of power are asked to address this essential work that has historically been reserved for women. A few weeks later, Vice President Kamala Harris proposed a plan to prevent families from spending more than 7% of their income on child care.

Hearing about child care as a central issue in a presidential election is not politics as usual. It is, in fact, the culmination of the work of generations of feminist activists.

Valuing care work may not be the first thing that comes to mind when we think of feminism. American schools often teach feminism as a struggle for freedom from housework and care, led by largely white, middle- and upper-class women like Betty Friedan. Through this lens, the success of the feminist movement should be measured mostly by the number of women who pursue their careers.

But there were other types of feminism before and after this focus on paid work. In 1942, union organizer Kitty Ellickson wrote an influential essay about a term for the reality women still lived in, the “double day”—doing most care work while also working for pay is doing two jobs for the price of one.

The solution, Ellickson wrote, is for the women’s movement to demand that employers adapt “the world of men to women.” From this perspective, true gender equality meant questioning the idea that “men’s work” outside the home was more important than the work done at home. It also means shorter work days and access to affordable childcare. Not surprisingly, these ideas arose out of the labor movement, as women who worked in mines and factories were less likely to equate their jobs with emancipation.

Nor was work an attractive feminist vision for those whose jobs were outside the home…in other people’s homes. Sometimes this work was not paid at all: this country’s first domestic labor force was made up of enslaved women. Even today, it is often women of color who bear the unprotected, poorly paid domestic labor that remains when middle- or upper-class women leave for the office. More than half of domestic workers nationwide are women of color, according to one 2022 report, with Black and Latina women overrepresented.

Dorothy Bolden, a black domestic worker in Atlanta and a contemporary of Friedan’s, began washing diapers for her mother’s employer at the age of nine. It fought the invisibility of care work and care workers, organizing 10,000 domestic workers starting in the 1960s. For higher wages and better working conditions. She told Georgia lawmakers that janitors and nannies have families, too: “I have to get my kids dressed.”

During the 1970s, welfare rights activists went further, arguing that mothers deserved government benefits: if care work was real work, society needed to recognize its value in return for pay. Leaders of the National Welfare Rights Organization, including Johnny Tilmon, pointed out that while our culture views white housewives as ideal for full-time care of their children, leaders demonize Black mothers as a drain on the system dependent on welfare. As mainstream feminist organizations came to the defense of universal day care centers, welfare rights organizers demanded justice for those who would staff these centers, warning of the creation of an army of “institutionalized, partially self-employed mothers.”

This combination of ideas advanced by black women’s leaders—that family care work needs financial support, and that professional care workers need fair working conditions—speaks to a profound vision of racial, gender, and economic equality that was often lacking in mainstream feminism.

Although Harris has sometimes been criticized for shifting issues, he has long advocated for family welfare benefits as well as justice for care workers. As a California state senator, in 2019 she sponsored the Domestic Workers’ Bill of Rights, which would have guaranteed overtime pay, sick days, meal and rest breaks, as well as launching a study into how to achieve health care, retirement and other benefits. More easy. Her recently proposed 7% cap on child care expenses may fall short of the pensions for domestic workers and guaranteed income for single mothers that extremists once envisioned, but her choice to highlight this issue could shift our national consciousness toward progress.

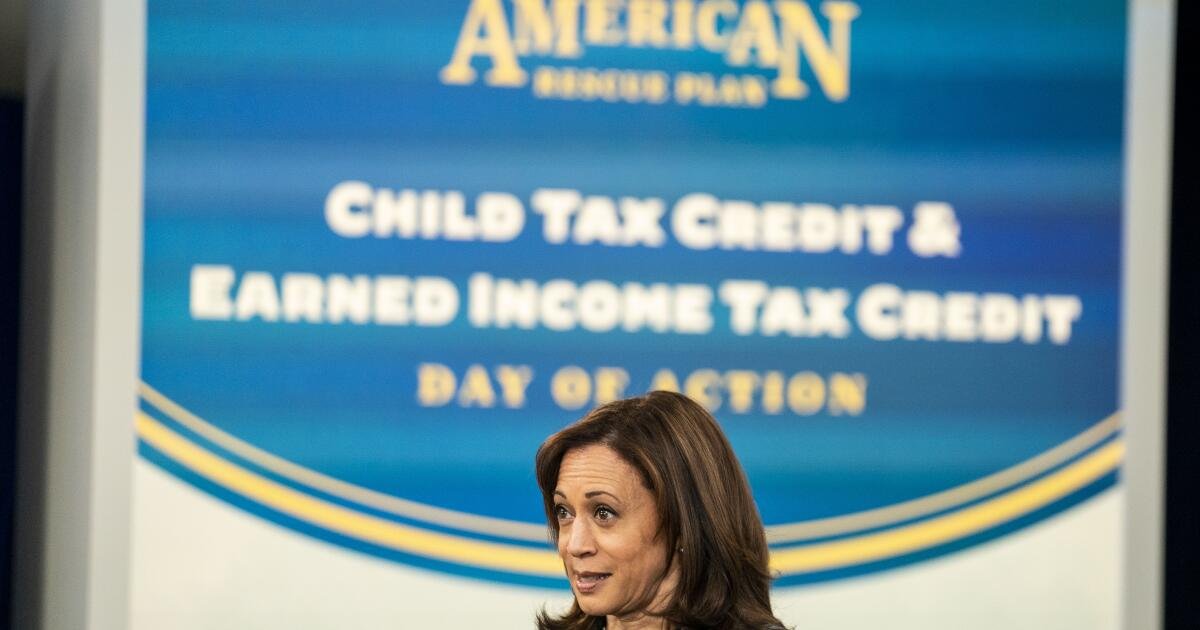

Harris has supported care work without enshrining the “traditional” family, focusing on policies that would help a wide range of families such as paid family leave, affordable long-term care, and expanding the child tax credit. This is consistent with the National Welfare Rights Organization’s insistence that single-parent families deserve the same respect as other families, and with the organization’s call for policies to assist caregivers regardless of their family structure.

Both Trump and his running mate, Senator J.D. Vance, have expressed support for expanding the child tax credit. However, Vance attacked working women and childless women, disparaged daycare and suggested that bringing in grandma or grandpa was the answer to childcare costs. In addition to targeting and shaming women, these statements make it difficult to believe that a second Trump presidency will recognize that paid care work is a pressing need for many types of families and that care workers deserve equal rights.

True equality for women — all of us, regardless of race or class — depends on the support of parents and the struggles of professional care workers, most of whom are women, who, in the words of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, “make all other work possible.” Perhaps this kind of feminism has finally reached its day.

Sirin C. Khader, a professor of philosophy at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York and Brooklyn College, is the author of Fake Feminism: Why We Fall in Love with White Feminism and How We Can Stop It.