In summary

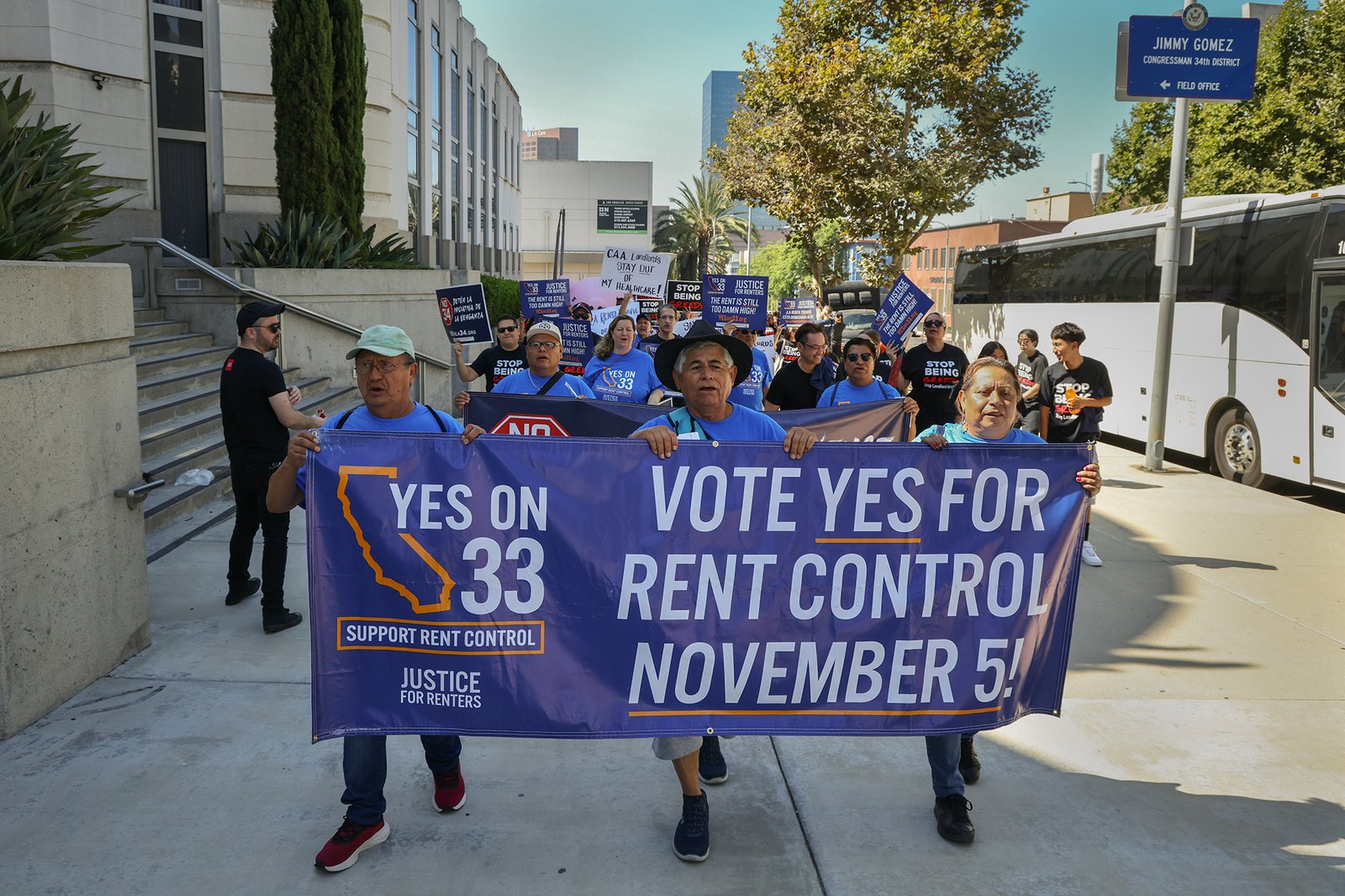

As voters consider whether to allow local governments to expand rent control, elected officials in San Francisco and Los Angeles have already shown interest in doing so. In other cities, local laws could automatically cap annual rent increases on some single-family homes and newer apartment buildings if Proposition 33 passes.

Welcome to CalMatters, the only nonprofit newsroom dedicated solely to covering issues that affect all Californians. Sign up for WhatMatters to receive the latest news and commentary on the most important issues in the Golden State.

Leah this history in spanish

If Californians vote to approve a rent control measure on the ballot, thousands of Berkeley renters could immediately see new limits on how much landlords can raise their rents each year.

“Families living in units that are not suitable for them will have the opportunity to move without losing affordability,” said Leah Simon Weisberg, a longtime tenant advocate and chair of the city’s rent board. “For some people, it will keep them home.”

This same scenario, where the city could cap rent increases on single-family homes, apartments that are more than 20 years old and units rented by new tenants, is a nightmare for Christa Gulbransen, who heads the Berkeley Realtors Association, which represents landlords in the city. “We’re going back to the 1980s and it’s not just roller skates or rainbow headbands, it’s going to be a lot worse,” she said.

Proposition 33 would repeal a state housing law that limits how cities regulate rents, allowing local governments to make that decision. Most California cities won’t see immediate change. But in a few cities like Berkeley, local ordinances already contain language that allows for much more extensive regulation than current state law. In those cities, and in others where left-leaning elected officials have expressed public support for expanding rent control, renters could see the quickest benefit from Proposition 33 — and landlords could quickly feel the headache.

More than 30 California cities already place some limits on rent increases, with caps ranging from 3% to 10% per year for covered units, some of which are tied to inflation.

“For some people, it will keep them home.”

Leah Simon-Weisberg, president of Berkeley’s Rent Council

At the state level, California caps rent increases for apartments and homes owned by businesses more than 15 years old at 10% per year — a rate that tenant advocates said could still be too burdensome on renters.

Get Ready to Vote Get Ready to Vote Our nonpartisan voter guide makes it easy to understand what’s at stake. Our nonpartisan voter guide makes it easy to understand what’s at stake.

Some of those local ordinances were previously more stringent. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, concern about rising housing costs led a few cities to limit rent increases even when a new tenant moved in — known as vacancy control. But the 1995 law that Proposition 33 would repeal, known as the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act, put an end to that, along with any rent controls on single-family homes or those built after 1995.

It’s the ban on rent control for single-family homes that bothers Melvin Willis, a city councilman in Richmond, one of the few remaining working-class cities in the Bay Area. He said that many families in his area rent their homes, and some complain to him about significant increases in rents.

“It’s a difficult conversation to have when someone says, ‘My rents have increased, but we have rent control,'” he said. Willis remembers explaining to a family doubling their rent that the city’s 3% cap on rent increases didn’t apply to single-family homes. “I’ve had this conversation a few times and it just doesn’t feel right,” he said.

Richmond’s rental code excludes any dwelling that is “exempt from rent control pursuant to the Costa-Hawkins Rental Dwelling Ordinance.” Willis and other affordable housing advocates argue that this means that if Costa Hawkins disappears, single-family homes and other housing excluded by state law would automatically fall under rent control.

Nicholas Traylor, executive director of Richmond’s rental program, was more cautious. He said the ordinance could refer to units that are actually exempt under Costa Hawkins, or just the types of units, such as single-family homes, that Costa Hawkins excluded. If Proposition 33 passes, the rental program’s general counsel would have to recommend how to proceed, he said.

In San Francisco, city supervisors avoided that ambiguity by unanimously passing legislation that would be activated if Proposition 33 passes, raising rent control to an estimated 16,000 additional units. Mayor London Breed said she would sign it if the proposal is approved, the San Francisco Standard reported.

San Francisco belongs to a group of cities — along with Berkeley, Oakland, Los Angeles, and the Southern California cities of West Hollywood and Santa Monica — that have long-standing rent controls that are particularly restrictive under current state law. This is because Costa Hawkins grandfathered in any exemptions they had for more newly built units. So in San Francisco, apartments built after 1979 are considered “new construction” and exempt from rent control. In Los Angeles, it’s 1978.

“It is completely arbitrary that we can impose rent control on buildings as of 1978, but we can’t do it in 1980,” said Hugo Soto Martinez, a Los Angeles City Council member, referring to the city’s homelessness crisis. “Every year we continue to lose more of our rent-stabilized housing.”

Last week the council passed a resolution, drafted by Soto Martinez, endorsing Proposition 33.

This type of action by cities upsets property owners, who point out that utility and insurance costs are rising, and in some cases exceeding inflation.

In an email newsletter sent to housing providers on Friday, real estate firm Borenstein Law warned its clients that “there is a real possibility that Proposition 33 will pass due to the widespread belief that rents are too high.”

The company urged landlords, in preparation for the potential shift in policy, to “raise rents to market rate if landlords are able to do so” and to consider offering voluntary buyouts to tenants paying below-market rents.

“Every year we continue to lose more of our rent-stabilized housing.”

Hugo Soto Martinez, Los Angeles City Council member

Opponents of Proposition 33 have also raised concerns that cities will enact rent controls so strict that they will stifle new housing construction at a time when the state needs it most.

“The state has done a lot to remove barriers to housing construction and incentivize affordable housing construction, but Proposition 33 will give NIMBY cities a really powerful weapon to get around those rules,” said Nathan Click, a government spokesman. Not in 33 campaigns.

But San Francisco shows that, given the flexibility needed to craft new policies, even cities with a strong history of advocating for renters may opt for more modest rent control changes that can garner broad political support. Board of Supervisors Chairman Aaron Peskin had originally proposed that the city expand rent control to include housing built before 2024, but he took that back to 1994, an idea that received support from both the progressive and moderate wings of city government.

The expansion of local rent control “will also depend not only on tenant and housing organizations, but on other civil society organizations in those communities,” said Shanti Singh, legislative director of Tenants Together. “Would they be ready or willing to push for that?”

Manuel Pastor, director of the Equity Research Institute at the University of Southern California, said his research shows that stabilizing rents without controlling vacancy helps prevent displacement by keeping rents affordable, while avoiding a slowdown in new construction where there are still incentives to build.

If cities start capping rent increases when new tenants move in, the effects become more difficult to predict, he said. That’s partly because the last time California cities experimented with vacancy control was more than 30 years ago — when more multifamily housing was built and before the technology boom put unprecedented pressure on Northern California’s housing market.

One thing likely, he said, is that California will see geographic variation, with more developed coastal cities setting stricter rent limits while inland cities with more moderate policies seek to attract development with looser rules.

“If proponents of Proposition 33 think this will solve our housing crisis, they are wrong,” he said. “If opponents of Proposition 33 think this will lead to a housing Armageddon, they are also wrong.”

Related to

“CalMatters sets high standards, providing personalized coverage and expert reporters who ask tough questions and hold our leaders accountable.”

Marcella, Montrose

A distinguished member of CalMatters

Members make our mission possible.

div {flex-basis: unset !important;flex-grow: 1 !important;}.single-post .cm-cta.cm-cta-testimonial h6{text-align: left;}.cm-cta.cm-cta -Certificate .cm-cta-center-col{align-items: center !important;gap: 12px;}.cm-cta.cm-cta-testimonial .primary-cols.wp-block-columns{gap: 40px;} cm-cta-testimonial .btn-col {flex-base: auto;}.cm-cta.cm-cta-testimonial .wp-block-buttons{min-width: 98px;}@media screen and (max-width: 782px){.single .cm-cta . cm-cta-testimonial .cm-cta-center-col > div{flex-basis: min-content;}.cm-cta.cm-cta-testimonial > .wp-block-group__inner-container{grid-template-columns :auto;}.cm-cta.cm-cta-testimonial .wp-block-button.btn-light .wp-block-button__link{padding: 7px 24px;}div.cm-cta.cm-cta-testimonial{ padding : 16px;}.cm-cta.cm-cta-testimonial h6{text-align: left;}.cm-cta.cm-cta-testimonial .primary-cols.wp-block-columns,.cm-cta. cm-cta-testimonial .cm-cta-center-col.is-not-stacked-on-mobile{gap: 16px;}.cm-cta.cm-cta-testimonial .btn-02-detail-05{font- Size: 12px;line-height: 16px;}.cm-cta.cm-cta-testimonial .mob-p-12{padding: 12px;}}]]>