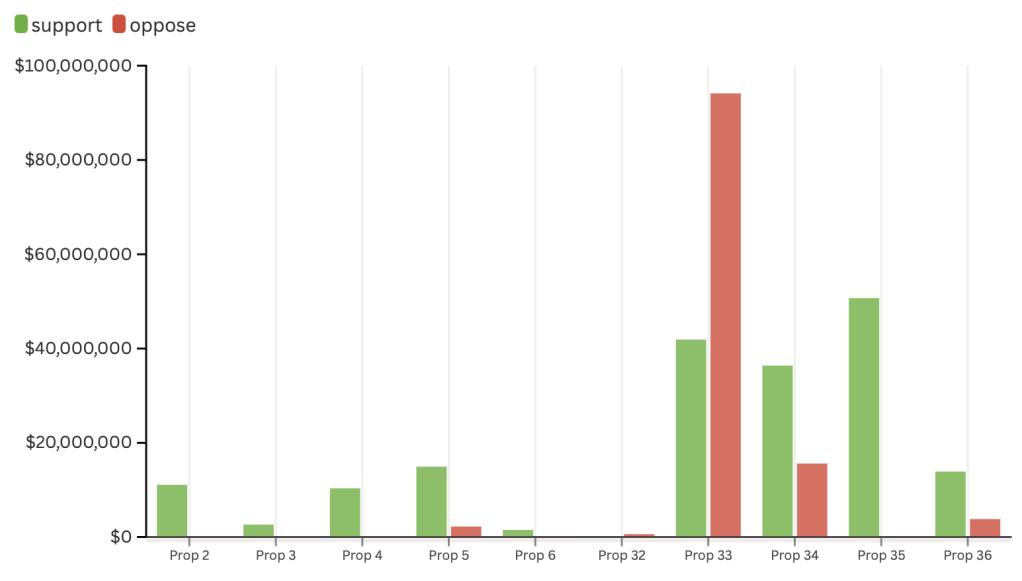

The 10 proposals on the California ballot this year are responsible for a spending frenzy, with campaigns spending more than $300 million trying to get their messages out to voters.

By far the biggest fundraiser this year was opposition to Proposition 33, which would allow cities and counties to impose strict rent limits on all types of housing. As of October 19, the end of the pre-election campaign finance reporting period, the 33rd Home Committee had raised $77 million, most of it from the California Apartment Association.

Since then, the condo association has dropped an additional $11.5 million into its committee’s coffers, with “No to Prop 33” ads warning it could increase housing costs that are still being shown on TV and streaming services, hoping to sway those who haven’t They do it yet. Fill out their ballots.

Those ballots, which probably still hang on the kitchen tables of many of California’s 22 million registered voters, include several pages devoted to proposals that made it through the Golden State’s complex, century-long direct democracy process.

“We are asking Californians to make decisions on some very complex matters,” said Melissa Michelson, a political science professor at Menlo College.

“Political scientists will tell you that direct democracy is very popular, but it’s not necessarily a good way to make policy, because you can only vote yes or no,” Michelson said.

Ten proposals is an average number to appear on the ballot, but this year’s measures are fighting an uphill battle, “overshadowed by the presidential race because it is so contentious,” according to Sean Bowler, a political science professor at the University of California, Riverside.

“These policy proposals must make their voice heard above all the noise of the presidential race — and that is difficult,” Bowler said.

The total spent on proposals this year falls short of the record $357 million raised by online gambling companies and tribal casinos for a pair of measures that would legalize sports betting in the Golden State in 2022.

Before that, the state’s most expensive proposal was Proposition 22 — when Uber, Lyft and DoorDash paid more than $200 million in 2020 to defeat a state law that treated their drivers as employees.

At the end of October, the California Secretary of State reported that just over 6 million votes had already been cast.

While opposition spending was twice as high, Proposition 33 also inspired the second-largest “yes” spending, with nearly $42 million spent supporting the proposal through October 19.

Proposition 35 has received the most spending of all the measures, with more than $50 million spent, and no opposition spending to speak of. The proposal would make permanent a tax that helps pay for Medi-Cal, the state’s Medicaid program that provides health care to low-income Californians.

“It’s an incomprehensibly large sum of money,” Bowler said. But the job is to inform voters [their message] …And there will be 20 million voters.”

Some more complex or specific proposals need to put more effort into communicating with voters, and that’s where endorsements from environmental groups or local unions help people decide, according to Bowler.

On the other hand, some proposals, such as Proposition 3, are clearer – and generate less spending.

Proposition 3 would overturn Proposition 8 of 2008, which defined marriage as between a man and a woman. Since same-sex marriage was legalized in California in 2013, and nationally in 2015, it has become more of a symbolic proposition and less money is spent because people already know how they feel.

“If you’ve already made up your mind, and this is a pretty clear-cut issue, it doesn’t matter how many ads you get,” Michelson said.

And for more complex suggestions? Michelson suggests that you follow the money. “Looking at where the money is coming from from each side can sometimes be more educational than the name of the proposal, or watching the ads.”

The $300 million equates to $13 per registered voter, which is a trend. “In the last two sessions, these huge sums of money have been spent over and over again,” Michelson said.

Bowler compares it to the advertising budget of a fast food chain like Domino’s but with additional challenges. “We like pizza, we don’t like politics,” he said.

Originally Posted: November 3, 2024 at 6:04 AM PT